The Year China Stopped All the Games

Looking Back on Tencent’s Limbo

The video, one of the first that I’ve made, is linked below.

Author’s note: I have been thinking about this one ever since the news about Alibaba and Ant Group started coming out. It is a bit interesting to see how the Chinese Government have exercised power over these two companies in the past few years.

When the government filed anti-monopoly charges against Alibaba, I noticed that they also hit at a Tencent affiliate but did not do anything with Tencent or WeChat itself. I wonder why that would be the case when WeChat does some of the same behaviors as Taobao. For example, I recall that WeChat won’t send Taobao links. Imagine the uproar if WhatsApp won’t deliver an Amazon link!

I wonder if the Government already feels that they have “made their point” with Tencent after this year-long game freeze saga. Or maybe there’s more coming that we have yet to see.

I hope to have another video coming in the future about WeChat and Tencent’s monopoly. Stay tuned for that one.

Want to help support the Asianometry YouTube channel? Check out the Patreon and help me pay for all this coffee I spend at the cafes I go to write.

This is the story of how Asia’s biggest company grew like a weed for 16 years until it and the entire Chinese video game industry collided head-on with the power of the Communist Party. Guess what happened. Today, we are going to talk about Tencent.

Imagine a single app that encapsulates your entire life — it greets you in the morning, hangs with you all day, and is the last thing you see at night. The one place where you buy things, talk to your friends or family, share presentation files with your coworkers, order dinners, pay taxes, and fulfill your bills. That is WeChat. It is the first thing that Chinese people install on their new phones.

Its ecosystem is so powerful that it has basically bridged the divide between iOS and Android. It is a piece of software that basically runs a nation and it belongs to a private firm called Tencent. Tencent has leveraged its prize asset into a network of investments that makes it like Facebook, WhatsApp, PayPal, Electronic Arts, and a private equity fund all in one.

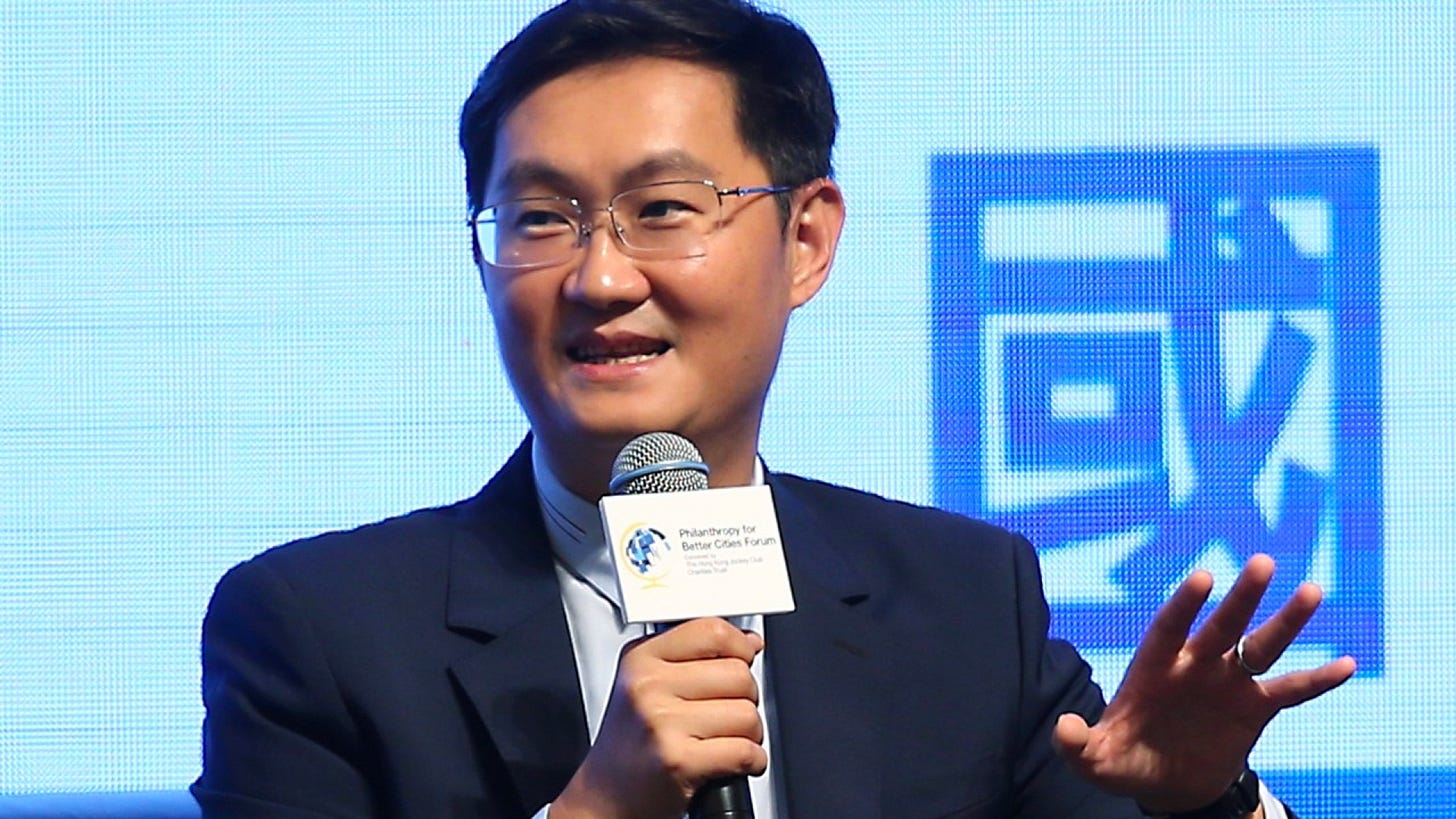

Founded in 1998 by five people including Ma Huateng — who runs it now as CEO — Tencent grew quickly with its 1999 desktop messenger product QQ. The QQ penguin icon is pretty well-known throughout China. This desktop business helped Tencent grow well at the start, but the company really took off in 2011 after the release of its mobile messenger WeChat.

WeChat

WeChat exploded on the back of the QQ desktop messenger and eventually outgrew it. Joining a world dominated by other mobile players, WeChat developed into a monopoly partly through rapid product updates. It was more than just an extension of the QQ desktop messenger.

Author’s note: Looking back at it now, I feel like I gave too little light to the point that Tencent already had a dominant desktop messenger at the time WeChat came out. I gave a lot of emphasis to all these new, cool features and how the team worked so fast. It gives a mistaken impression that such features were the deciding factor in making WeChat dominant. Maybe that’s true, but at best it downplays the crucial leverage point. Tencent migrated their existing users from QQ to WeChat and that mattered more than “voice messages”.

In fact, they were built by different teams. They had originally tried to simply port the QQ product for the phone but could not make it work. So a small product team led by a guy named Allen Zhang went back to the drawing board and rethought every assumption. Weixin was born and was later given the English name WeChat. The small product team moved WeChat forward with startup speed and a flurry of new product features.

First was the support of voice messages, which made it much easier for people to convey a long message without having to type it all out.

Next came Moments, a way to share images and text with your friends. This became like the Facebook News Feed with the caveat that only your friends could see what you posted on Moments. It allowed Chinese users to express themselves freely.

Then after that came Official Channels, which gave verified brands a way to directly communicate with users. These lived right in the WeChat chats interface next to your chats with school friends, family and coworkers. Fashion bloggers took up Official Channels and became influencers, making money through their posts.

This monetization came through the WeChat Wallet, which allowed people to pay money for things and to people. Through this came the ability to do all the things that WeChat is today famous for.

WeChat’s next hyped product feature was the mini-program, a lightweight app living within WeChat itself. Most of these apps are simple JavaScript webpages less than 10MB that can enrich people’s experiences without having to leave the WeChat screen. More than a few companies have realized the implications of having small mini-apps within WeChat. Why download an iOS app or an Android app off the Google Play store?

How WeChat Makes Money

Today, WeChat has over 900 million active users — almost all of them in China. But WeChat is free and most of it integrations are free. So how Tencent make money?

Line, another massive messenger in Japan, pioneered revenue through the sale of stickers and other value added digital products. But WeChat doesn't really do much of that. So how does this company make some $40b in revenue? There’s a blog out there famous for attacking the quality of Alibaba’s revenues and they wrote an article from a long time ago asking about Tencent’s revenues. They counted up all the digital assets that QQ supposedly sold and asked with more than a little snark this very same question.

So where does Tencent’s money come from?

There are a few things. Digital products. Movies. Advertising. They also make a lot of money through investments in companies that take advantage in WeChat’s networks. But the majority of the money comes from games. Tencent is the world’s biggest video game company by far. They own some of the biggest and profitable games in the world. That includes majority stakes in Supercell (makers of Clash of Clans), Riot Games (makers of League of Legends), and a 40% stake in Fortnite maker Epic Games — a stake worth some $6 billion after Epic recently raised funds from private equity group KKR at a $15 billion valuation. (Just for good measure, they also own a big stake in the company that making PUBG too.)

The company localizes some of these games and ports them for release into China — which has led to one of the biggest games in the world that you have never heard of: Arena of Valor … or also Honor of Kings … or Realm of Valor. It is pretty much a mobile port of League of Legends. Tencent Games made it after Riot declined making League of Legends available for the mobile.

Why would Tencent — which has WeChat — want to get involved with games? Because games are a high cash flow business that play on our monkey brain addictions. With the use of microtransactions, free to play games can generate boatloads of cash. They in fact, generate some 20x more than the traditional business model of selling games for money. The biggest cost after the game is developed is getting users to play the games. That is where WeChat comes in. WeChat is basically a big user acquisition tool for Tencent’s games and other applications. They splash big game ads right on top of your chats. Irresistible! Those games in turn bring in money like video games have never done before.

And yes people actually do spend money on these games. Like the author of the Deep Throat IPO blog, I have an accounting background. His stuff on Alibaba seems pretty solid but I found his analysis of Tencent shallow. His specialty appears not to be in digital video gaming. The thrust of his analysis was to count up value added service offerings in the annual report and their subscriptions, find a discrepancy between those and the revenue number and then stamp them a big fat red “fraud”. If that is the case, then a lot of American companies like Zynga, King (maker of Candy Crush) and Epic Games would probably be frauds in his book too. There can be a lot of accounting haggles between video game companies and their accountants but those often arise from conflicts on how to book expenses and revenues over periods of time. But there can be no dispute about the existence of the cash flows. Cash flows often come through a verified third-party (the App Store usually) and it is a business model that many other public companies have. Any accountant knows that cash is king because it is easily verifiable and Tencent generates plenty.

The Freeze

By the end of 2017, Tencent had become Asia’s biggest company, worth over $500 billion. The company had its game business growing faster than ever before. WeChat began exploring the advertising space, with its Moments feed starting to grow its advertising revenue. Investors dreamed of an advertising business the same size as Facebook’s (another $40 billion!) Its portfolio had public company investments in JD.com (e-commerce), Meituan-Dianping (food delivery), and China Literature (which went up 90% in its Hong Kong IPO in 2017). Everything was breaking right and it seemed like nothing go wrong.

Well, until it did. And it starts as it always does with the Chinese Communist Party. And as with all things related to the Party, it happened without warning or care for the businesses of those affected.

It started with new regulations that forced Tencent to tie people’s actual identities to their video game IDs. Then the company had to tighten further by placing identity checks and an age floor for its Arena of Valor game. Someone under 18 would not be able to play the game for more than a few hours.

But that fell short of what the Party wanted so then came the real big blow. In March 2018, the Party froze every video game release in the entirety of the country. China is the only country in the world where a video game needs to have its content and mechanics approved by the state. In 2017, it approved 9,651 video games for play in the Chinese market. In January and February, it gave 1,982 licenses. Then … nothing.

The license approval process had been already so complicated that no foreigner developer could hope to get approved without a local partner (Tencent makes money by being such a shepherd for games like PUBG). It is a two-step process. The first step is to allow the game to be released. The second process is to allow the monetization of the game with micro-transactions. This second process, which is overseen by China’s General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP), is the one that got frozen. It was ostensibly so to restructure the state game and media content regulatory agency, ensconcing it deeper within the Party apparatus so to tighten its grip on content and ideology. But even after the restructuring had supposedly completed approvals remained frozen.

Some games were left literally in the lurch. PUBG for example got the first approval, so it was released and became immediately quite popular. However, this second approval did not come and the Party said nothing about when to expect them to resume. Big companies and small companies alike in the $40 billion industry were affected. What can you do if you are in this industry and the Party ignores the pleadings of even the WeChat people?

On the August 2018 earnings call, Tencent came in with its first profit drop in a decade and the President Martin Lau made it clear whose fault it was.

“From a revenue growth perspective, gaming is a key area of weakness and our biggest game is not monetizable. The administration is also aware of the fact that because of the restructuring it’s now affecting the industry as a whole."

You got to imagine the feelings behind a statement like that.

That day in August 2018, the stock dropped 3% and kicked off a market decline that would eventually top $200 billion. Interestingly enough, fellow Chinese gaming company NetEase had pre-announced this massive industry event in an earlier earnings call when the CEO said that a “government bureau restructuring was causing a delay in game approvals”. That day, Tencent stock was up 2.4%. Either nobody listened to that NetEase call or nobody thought, “Hey, this massive industry thing that this one Chinese gaming company pointed out and caused them to miss earnings might also be affecting the biggest Chinese gaming company of them all!” Market efficiency, my butt.

It was not until December 2018, nine months after the freeze, that the industry regulator began to approve games once more for release and monetization. The Communist Party Propaganda department would now be overseeing the process of issuing license numbers and allowing monetization. Tencent stock jumped 4% on the news. The process has been changed though — with lists signifying what is good or bad, checks on the video game AI itself, and censorship. A few weeks later, the first 80 or so games had their approval though none of them were Tencent’s.

This should be good news except for one thing. During the wait for approvals to restart, the Chinese economy began to slow. For whatever reason it might be, whether it has to do with the trade war or the excessive debt in the economy, growth slowed and the stock market turned. China Literature stock dropped more than 50% from its peak. Meituan began to do layoffs. All of these sucked value out of Tencent’s constellation of valuable investments.

Too Big For Its Own Good?

So is this a story of a company growing too big for its britches and thus getting a smackdown from the Communist Party? Or are we looking too much into it? With the Party you can never know for sure. The Party is an authoritarian power that considers its own rule the foremost thing to uphold. They are more familiar with the concept of “killing the chicken to scare the monkeys” and Tencent is a really big chicken.

Yet at the same time the Party also runs a government, which means listening to the people and responding to social issues with new regulations. And it does seem like video game addiction is a real problem with real consequences that has to be addressed. Parents were complaining that the video games were too violent and game addiction was affecting kids’ lives. There had been studies that the high rates of myopia in Chinese kids could partially be a result of them staring too much at phone screens at an early age. As the Party spokesperson said in the December speech announcing the restart of video game licenses:

“We hope through new system design and strong implementation we could guide game companies to better present mainstream values, strengthen a cultural sense of duty and mission, and better satisfy the public need for a better life.”

The Party has also hit other companies hard with its new focus on proper propaganda messaging. It shut down downloads of a service by rival Toutiao that let users share naughty jokes and videos. It also ordered Toutiao itself to clean up its act — prompting the company to hire some 10,000 to do self-censoring of stories and the CEO to write a personal apology note to the government.

Tencent remains a centi-billion dollar company and the company seeks to get even closer to the Communist Party. Its CEO has made several speeches praising the centrality of the Party and suggesting several new ways in which WeChat can be put to use in helping the government’s goals. These include real name policies and social credit tracking like those fellow mega-tech company Alibaba has. Tencent is a private company, but it knows that it now exists in an era where more than ever needs to demonstrate its usefulness to the Party.