SkyWater Technologies: America’s Semiconductor Foundry

Author’s note: If you want to watch the video you can below

I probably missed out on a few opportunities to add some Star Wars references here. And yes I miffed the pronunciation of St. Louis. I apologize to my fellow Americans.

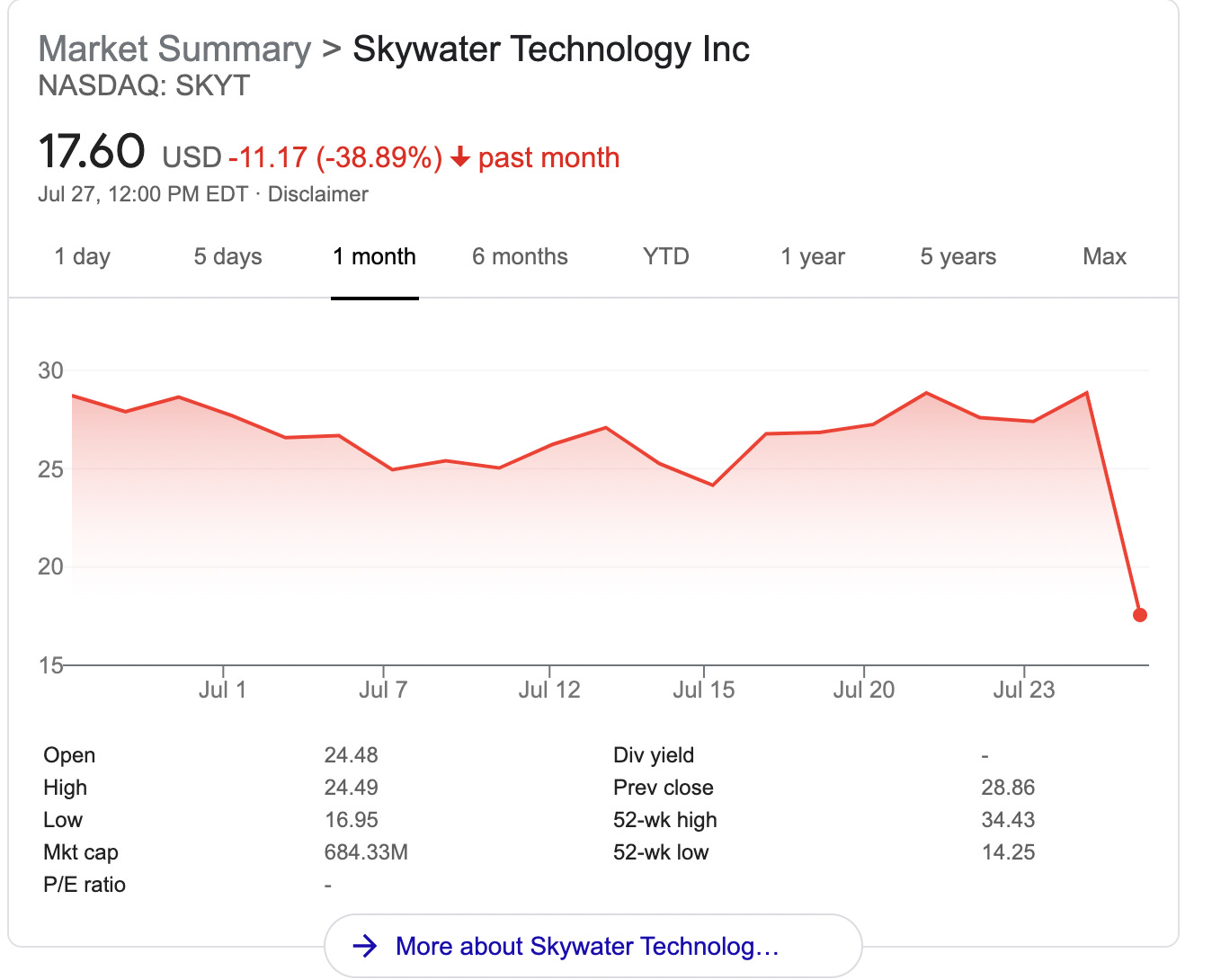

Let’s get the first part out first. The stock is down bad after announcing preliminary Q2 results (where it turned a quarterly loss) and that they are going to invest $56 million in their Minnesota fab. This is why Asianometry is NOT a stock investment channel. If you buy a stock based on something you’ve learned from a video here, well, don’t. I will be seriously disappointed.

It looks like the strategy is to gain ATS revenue from co-developing new technologies (like Rad-hard) with customers and then transition them to Wafer Services, gaining revenue there. Good strategy but the industry is no rougher than it was when I did the video. It is likely going to get more competitive with all these other companies ramping up their own US investments, but as of Q1 the margins are holding at 20% so maybe it won’t be too bad.

The company is probably going to need to sell stock to fund their own big investment push. As for April 2021, their main funding source was a Revolver with Wells Fargo, which had only $19 million left.

I want to talk about one of the few pure-play foundries in the United States and a 2021 IPO: SkyWater Technologies.

Bloomington, Minnesota-based SkyWater is a US-owned pure play semiconductor foundry that focuses on custom development services, volume manufacturing and advanced packaging. They seek to offer a complete suite of services to their clients.

Its Minnesota fab is one of seven American wafer fabs with 1A accreditation in Defense Microelectronics Activity from the Department of Defense. And is the only such foundry controlled by American investors.

Considering the recent interest that people have had in semiconductors and having semiconductors made in the United States, I thought it would be appropriate to do a video profile on this interesting company.

Introduction

The company is relatively young. For all intents and purposes, it began in 2017 when Oxbow Industries, a private equity group in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, acquired the Bloomington fab.

Oxbow Industries has been around since 2004, with Loren A. Unterseher serving as the Managing Partner. Unterseher has had a long career in mergers and acquisitions and sits on the SkyWater board.

Oxbow owns several other companies, most of which I have never heard of, manufacturing things I never think about like control interface products and decorative inlays.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that of course. In fact, such things tend to be some of the best investments out there.

Oxbow started SkyWater for two reasons. First, the Oxbow investor group felt that the division was "under-managed". Which is a kind way of saying that we think management sucked.

And second, they saw a coming trend of semiconductor on-shoring. Especially in context of the contemporary America-first political climate. As we will discuss later on, capitalizing on close government ties is a critical part of their business and growth strategy.

The Minnesota Fab

SkyWater's 80,000 square foot Minnesota fab had been previously owned and operated by American semiconductor maker Cypress Semiconductor from 1991 to 2017. Located a few blocks south of the world-famous Mall of America, it is one of three such fabs in the state.

Cypress purchased the fab in the 1990s from Control Data Corp. Over the 25 years they owned it, the fab was upgraded from the 130nm and 90nm process nodes to 65nm.

Far from the leading edge - TSMC started offering 65nm in 2005 - but that is fine. Not everything needs to be 5nm. The fab largely produced very special, low-volume chips that did not suit the bigger foundry players.

Mixed-signal circuits are the plant's most important products. Called as such because they have both analog and digital circuits on them. They are good for IoT, cellular and automotive solutions.

Another product the fab makes is SRAM, a type of low-latency high-speed data access RAM not unlike DRAM but most frequently used as processor cache. Very niche. Very nice.

In 2017, the fab was sold to SkyWater for $30 million. Cypress wanted to pay down their debt and reduce their manufacturing costs by consolidating some production to their Austin, Texas fab. Oxbow's move to acquire and start SkyWater would save 400 high tech manufacturing jobs in Minnesota.

Side note. Cypress itself would later be acquired by German semiconductor maker Infineon.

At SkyWater's founding, the fab was capable of 12,000 wafer starts a month. This is assuming 200-mm diameter wafers and 30 mask layers. A wafer can have multiple mask layers projected onto it. The more layers, the longer it takes to do a wafer.

12,000 200-mm wafers a month is not a whole lot. For context, TSMC’s Gigafabs are capable of 100,000 300-mm wafer starts each month. But when you are making niche specialty chips, 12,000 is fine.

Growing an American Fab

Oxbow's first step in bringing the Minnesota fab up to speed had to do with management. The private equity group recruited a roster of experienced talents to run SkyWater. These include a CFO, CTO, Director of Operations and current President and CEO Thomas Sonderman.

Getting started would take time. SkyWater wanted to ensure that they could count on its former owner during the transition period. So Cypress Semiconductor signed a 3-year wafer supply agreement to buy chips from SkyWater while the startup got its legs under them.

If you know AMD and GlobalFoundries, then you would be familiar with these. If you want to learn more about that relationship, I encourage you to watch my video about AMD.

At SkyWater's founding, 97% of the company's revenue came from Cypress, with the rest coming from a company called Parade Technologies. A year later in 2018, SkyWater managed to add four additional customers, reducing Cypress's share from 97% to 60%.

The company also began collaborating with the US government to upscale its manufacturing techniques and eventually compete for government contracts. A few weeks after SkyWater's founding, the US Department of Defense deemed it a Category 1A Trusted Foundry.

Then in 2018, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, awarded a contract to a team consisting of SkyWater, MIT, and Stanford to develop carbon nanotube microelectronics.

A year later in 2019, the Department of Defense gave SkyWater a $170 million contract to make chips capable of surviving high levels of radiation. Such resistance in radioactivity - called 'rad-hard' - has useful applications in the medical, aerospace, and military fields.

The first allotment of money - $80 million - allowed SkyWater to add a third clean room to its Minnesota fab. This upgraded clean room would allow SkyWater to use copper interconnects and to hire another 30-50 engineers onto its staff.

In June 2020, the wafer supply agreement with Cypress/Infineon ended. By January 2021, the percentage of SkyWater's revenues coming from Cypress was 29%, down from the 40% a year earlier. A great improvement, but still a long ways to go.

Throughout this period, the Minnesota fab was SkyWater's single major asset. Then in January 2021, the company agreed to take over the Center for NeoVation facility in Osceola County, Florida. Their announced intentions would be to offer advanced semiconductor packaging services to their customers. Especially to the government.

Controlling both the front and back end facilities would allow SkyWater to offer a highly differentiated service to their customers at a good price and with a quick turnaround.

Business Strategy

In their S-1, SkyWater lists out their business and growth strategy.

First things first, they have to diversify their customer base. Despite having 36 individual customers as of January 2021, Infineon is still responsible for a quarter of their revenues. The next two largest customers represent another 30%. The core wafer fab business is still heavily concentrated and that is a risk factor.

Their pitch to potential wafer fab customers is their ability to do specialized, low-volume work with fast turnaround times. For instance, their core analog and mixed-signal wafer fabrication capability is still important and make a lot of sense in today's IoT and 5G era.

But they seem to be especially interested in radiation-hardened or 'rad-hard' applications. Makes sense since it is what that new third clean room is made for. The term has its own line in the growth strategy section and is specifically mentioned in the risk factors.

And of course, they want to heavily lean on close ties with the government. Government contracts helped pay for that third clean room, and their DMEA Category 1A accreditation is a big talking point in their marketing.

What SkyWater can do makes a lot of sense for the government. The Department of Defense is a big buyer of chips on the whole but the types they want are highly specialized and often do not make financial sense for large foundries. A chip that goes into a nuclear missile for instance is not really needed elsewhere.

Considering how important the government is to the company’s prospects, you might be wondering why the foundry doesn’t just go all in on government work. Despite what you may think, the US Government is not a sugar daddy. As Sonderman says:

“The goal of the government really is to stand up capabilities that can be used commercially. They want to have commercially viable entities … for their applications.”

This is a variant of the export discipline concept I mentioned in my Taiwan and TSMC video. If you want suppliers to be excellent, test their might in economic mortal combat by making them win business on their own.

A government stamp of approval could definitely help with that. Management believes that customers can appreciate the benefits of working with a foundry that is up to military-grade secrecy standards.

Conclusion

On the science and advanced technology side, the company is doing some interesting stuff. In addition to their work in carbon nanotube transistors, they are also making qubits for D-Wave's quantum computer.

It makes sense for them to experiment on these technologies, because you never know what might turn out to be a hit and such R&D can have larger benefits in the economy.

Financially, I would say that there is more good than bad. In April 2021, SkyWater held a successful IPO that had them sell 6.96 million shares at $14 a share, the higher end of the range. As of this writing in May 2021, the company is worth about $800 million.

Oxbow owns about 74% of that, so their $30 million initial investment plus whatever else they invested setting up the company is now worth $600 million. 20x or so return on investment over 4 years is a home run.

That's the good news. Now for the bad. The company's operating metrics might leave some pause. Gross margins, an indicator of pricing power, are hovering at less than 20%, a far cry from TSMC's 50%+. These margins are about the same level as your average fast food restaurant. As a result, the company turned an operating loss in 2020.

And heavy capital expenditures take a blow. SkyWater spent $90 million for upgrades in 2020, over 60% of their revenues and just barely more than their operating cash generated. They raised the capital for that by taking a Revolver loan from Wells Fargo and doing a $39 million failed sale-leaseback transaction of their property with their principal owner.

A famous investor once said: “When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for poor fundamental economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact”.

This isn’t a stock analysis but SkyWater seems to be an example of that. A decently well-run business in a rough corner of town. I would like to see them succeed. But the consistently low gross margins and constant need for capital expenditures are worrying. Such is the way in the low margin trailing edge foundry business.

They are leveraging every opportunity that has been given to them, including their close government ties. It seems like much of the company’s current value is in anticipation of big future government contracts. But I wonder if those contracts would be big enough to move the financial needle, drive growth, and make the company worth what people will pay for it in the long run.